Landscape History

River Brue sunrise – Joy Russell

The landscape of Somerset’s Avalon Marshes, and wider Levels and Moors, has changed greatly over time. Whilst the rate of change has slowed it still goes on as peat digging declines, nature reserves grow and farming changes. Here we take you through the history of the marshes’ landscape.

Dry land to sea

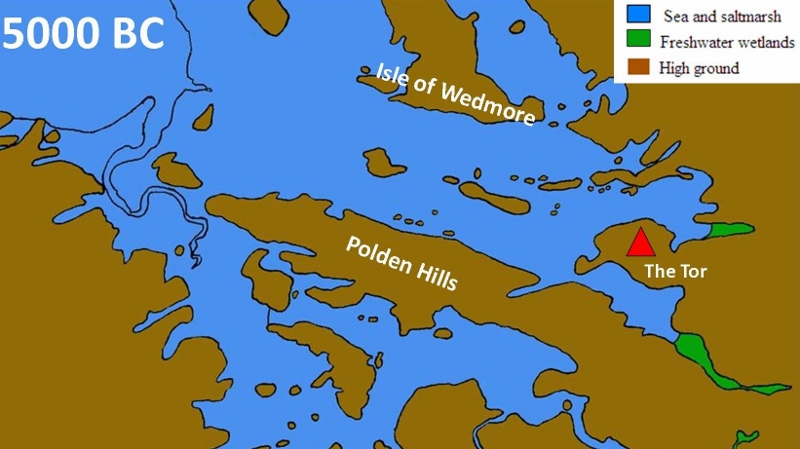

10,000 years ago, at the end of the last ice age, the Avalon Marshes did not exist. The area was a river valley with the coast lying beyond Lundy at the mouth of what was then the Severn estuary. As the glaciers melted the sea level rose rapidly until the only dry land was the Polden Hills and the islands of Wedmore, Burtle, Godney, Westhay and Avalon. The new coast was fringed with saltmarsh and large amounts of clay and silt were deposited in the former valley.

Around 6,500 years ago the rate of sea level rise slowed down and reedbeds started to colonise the increasingly shallow water. As the plants died their remains fell into the water. However, due to the absence of oxygen they did not decay – this was the start of the formation of the Avalon Marshes’ peat beds, the “Peat Moors”.

5000 BC landscape – South West Heritage Trust (adapted by AMLP)

Swamps, bogs and trackways

By the Neolithic period (4000-2300 BC) the area was principally a huge reed-swamp with freshwater pools and channels, rich in fish, fowl and wildlife. The surrounding hills and islands were much drier. Some of these are formed of solid rock but Burtle and other slightly raised areas are made from sand, gravel and sea shells, remnants of an inter-glacial period when sea level was 14 metres higher than today. These made good hunting bases and were used by the early farmers, who crossed the reed-swamp by building wooden track-ways, including the Sweet Track.

Over time, as the peat layers built up, brackish water was replaced by fresh water, and sedges and mosses started to colonise. Eventually trees such as alder, willow, birch and even oak grew on the drier areas and gradually replaced the reed-swamp.

This fen, or carr, woodland formed more layers of peat raising the ground until it was gradually replaced by a raised bog. Such bogs are dominated by sphagnum moss, heather and cotton grass. As the dome grows the bog becomes more and more impoverished of minerals, the only source of water is rain.

As these changes occurred crossing the marshes presented new challenges to Neolithic and Bronze Age man. Different types of track-way were built but lasted a few years only, lost by changes to the physical environment caused by climate change.

3500 BC landscape – South West Heritage Trust (adapted by AMLP)

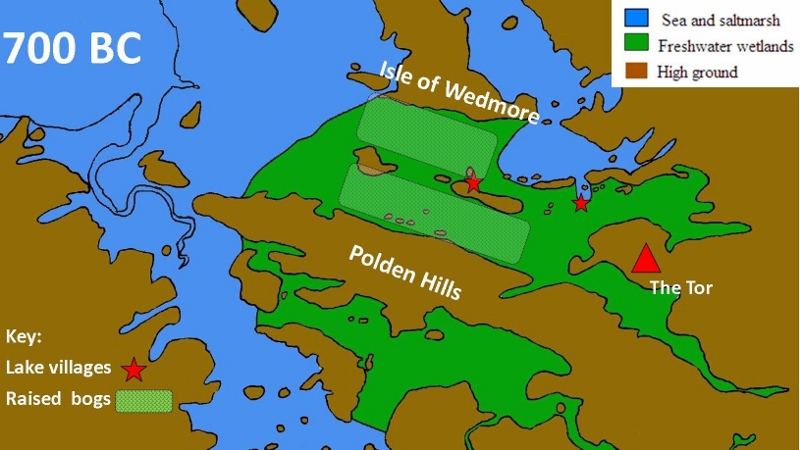

Iron Age Rivers

By the Iron Age conditions were far wetter and dugout canoes replaced track-ways as the main method of transport. The landscape was very different to the one we see today. The River Brue headed north from what is now Glastonbury, passed through the Panborough Gap and joined the River Axe. To the north and south of the islands of Meare and Westhay were two vast raised bogs. To the west was a network of saltwater channels linking “dry” land with the sea; these channels brought in silt and clays which eventually formed a slightly higher coastal belt (these are “the levels”). Iron Age man built their “Lake Villages” in locations to take advantage of these navigations.

700 BC landscape – South West Heritage Trust (adapted by AMLP)

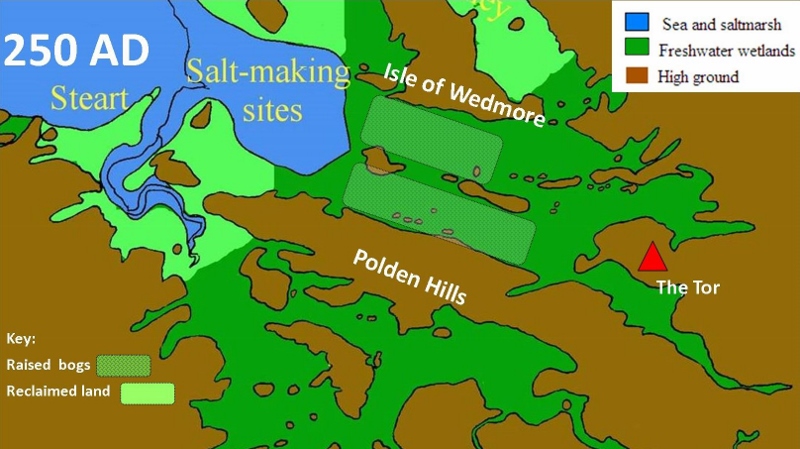

Roman Salt

The Romans exploited the resources of the Avalon Marshes but did not significantly change its landscape. The saltwater channels, underlying clays and peat were put to good use; salt was evaporated from the salt water using clay salterns heated by peat fires.

250 AD landscape – South West Heritage Trust (adapted by AMLP)

Medieval changes

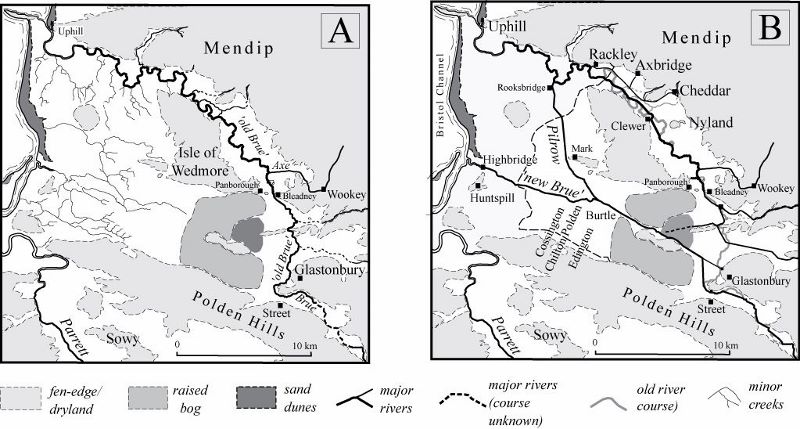

In medieval times almost all of the Avalon Marshes were controlled and exploited by the church; either Glastonbury Abbey or the Dean of Wells and the Bishop of Bath and Wells. During this period the rivers Sheppey, Hartlake and Brue were re-routed and canalised to flow almost due west to the sea. Meare Pool, a large expanse of open water north of Meare was retained as it was full of fish. Other parts of the area were enclosed and drained, which greatly increased their worth, but in the main the peat moors remained as ever growing raised bogs.

A – ‘Natural’ drainage system in the Early Medieval Period, showing the ‘old Brue’ flowing northwards into the Axe Valley. B – The Brue diverted westwards to Highbridge – Maps Prof Stephen Rippon, Exeter University.

The age of enclosure

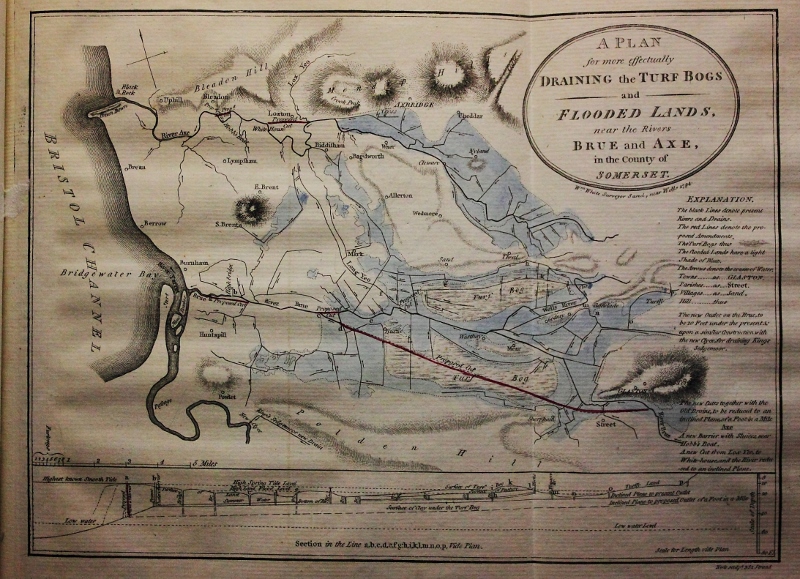

In the 18th and early 19th century parliamentary enclosure acts brought about a change from open common land to the regular network of ditches, rhynes, drains and droves that we see today. Even the most difficult areas of peat moor were drained and enclosed and the soils improved. However, winter flooding was still a regular occurrence; drainage was dependent upon the sluggish River Brue which cut through the higher clay belt of the coast (the levels) and which even today cannot discharge into the sea when the tide is high.

“A Plan for Draining the Turf Bogs and Flooded Lands” 1794 – John Billingsley

The 20th century – War and peat

The twentieth century brought two hugely significant changes. During the early part of World War 2 the Puriton munition works was built. This required huge quantities of water and was the very reason the Huntspill River was built. This channel, combined with the huge pumps at Gold Corner, solved much of the winter flooding problem in the area.

The second change was the growing horticultural use of peat. By the early 90s over a quarter of a million tons of peat were being extracted annually, leaving parts of the Avalon Marshes looking like an industrial landscape. Even areas of great conservation importance were dug. Somerset Wildlife Trust and the government’s Nature Conservancy Council worked to protect what they could.

Shapwick Heath – Natural England

Turning back the clock

In the early 1990s a huge campaign and a boycott of peat products forced a major change. The principal company, Fisons, pulled out completely; they handed large areas of land over to English Nature (now Natural England). Land was also passed onto Somerset Wildlife Trust and the RSPB and all three organisations created the reed-beds and lakes which are at the heart of the Avalon Marshes’ nature reserves.

The landscape today

The principal character of today’s landscape is one of rich green pastures criss-crossed with a network of blue water; ditches, drains and rhynes. However, look more carefully and the landscape is more varied than it first appears:

- The peat areas of Tealham Moor, Tadham Moor, Godney Moor, Edington Moor, Kennard Moor, Queen’s Sedgemoor and others have relatively few trees and no hedges, the fields are divided by “wet hedges” of ditches and rhynes.

- The western levels and moors which are slightly higher (if only a metre or so) with traditional hedges and more trees

- The areas of former peat working north and south of Meare. A landscape of reedbeds, lakes and wet woodland

- Sharpham and some other areas with their active peat extraction

- The “islands” with their villages and farms many built of local Blue Lias stone and some of local red brick manufactured from the underlying clays.

- Finally the Isle of Avalon – home to the busy town of Glastonbury, with stone and brick buildings of all ages, a countryside of small grass fields and orchards and last, but not least, Glastonbury Tor.

Explore the landscape

- If you would like some ideas on how to explore this landscape go to our Places to Visit section

- To find out more about the history and heritage of the Avalon Marshes go to our Heritage pages

- See the landscape as it used to be by visiting our Nature Reserves

The Avalon Marshes from the Nidons – Joy Russell