Glastonbury Lake Village

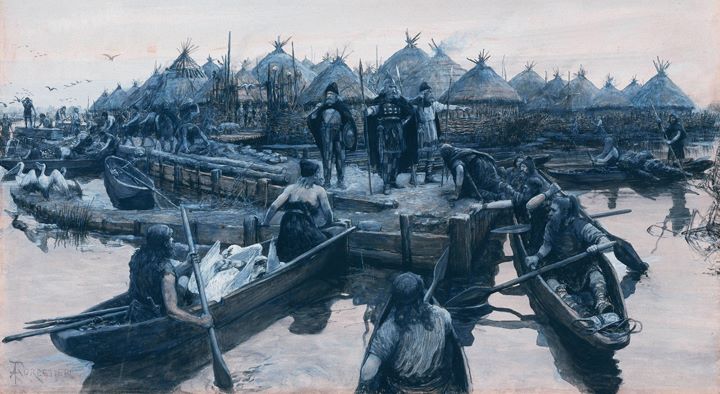

A representation of the landing stage by Amédée Forestier (1911)

In 1892 a young medical student from Glastonbury discovered an archaeological site on the nearby peat moors that was destined to become one of the most famous Iron Age sites in Europe. His name was Arthur Bulleid and he had recently read about the discoveries of prehistoric lake dwellings uncovered in Switzerland. Living beside a large area of wetland, Bulleid, an amateur antiquarian, thought that similar remains might exist in Somerset and spent four years looking for them until, in March 1882, he noticed a field covered in small mounds. Brief excavation showed that there were well preserved roundhouses with a varied array of everyday items of the late Iron Age.

National Importance

What Arthur Bulleid had discovered was the best preserved prehistoric village ever found in the United Kingdom, ranking alongside the great monuments of Avebury and Stonehenge in its archaeological importance. In 1892 Bulleid began an excavation at what soon became known as ‘Glastonbury lake village’. Working with Harold St George Gray, the curator of the Somerset Archaeology and Natural History Museum this continued until 1907.

The settlement that Bulleid and Gray excavated had not been built in a lake as the name suggests, but was in fact created at the edge of a patch of birch, alder and willow trees, in the midst of a large swamp of reed, sedge, open water and wet woodland that stretched all the way to Glastonbury. Through numerous channels in this swamp the sluggish waters of the River Brue slowly headed north, towards the Axe valley.

The village was habituated between about 250 and 50 BC. In total about 40 roundhouses were built during this time, with a maximum of some 14 at any one time. The enormous effort required to build and maintain a settlement in such a wet environment begs the question ‘why there?’ There is no definitive answer but it may have been because of the protection offered by the encompassing swamp and the importance of the fish and birds that lived in it. The site may have been located on an important water borne trade route from central Somerset to the Severn estuary. A dugout canoe was found in the foundations and another one in a nearby field.

Iron Age travel

During the Iron Age period the Avalon Marshes was much wetter than before and dugout canoes had replaced trackways as the main method of traversing the wetlands. The first reported canoe find was made in the early 19th century. Four other canoes have been found in the area, one in the foundations of Glastonbury lake village, one near Godney (used to be on display in Glastonbury Tribunal), another from the old vicarage garden at Meare and one found at Shapwick Station in 1906. The Shapwick canoe can be seen in the Museum of Somerset in Taunton.

Shapwick canoe / Replica canoes – SWHT

Iron Age living

Remains of bones and plants found at the lake village show that the villagers were eating a wide variety of food from both wild and domesticated species. The wetlands surrounding the settlement yielded perch, roach, trout, eels, frogs, numerous types of duck, pelicans, cranes, swans, herons, bitterns, otters and beavers. Lead sinkers for nets and baked clay sling shots show how these animals were caught. Dry land animals were also eaten, sheep being the most numerous. Wheat, barley, beans and peas were also present, possibly acquired in exchange for fish or wildfowl. Roe and red deer, wild boar, fox and wildcat were caught in the dry woodlands while the presence of puffin, cormorant and sea eagle suggest contact with the coast.

The range of everyday items of Iron Age life discovered at the village is staggering, examples are:-

- Vast amounts of plain and decorated pots of varying sizes

- Tools such as billhooks, saws and chisels which retained their wooden handles

- Other wooden items such as a ladle, a chopping board, a ladder and parts of a wheel.

- Woven baskets, carved and lathe-turned bowls stave built buckets and rectangular boxes made by steaming and bending wood into shape.

- Personal ornaments included bronze and iron brooches, pins and rings, shale armlets, glass beads, a pair of tweezers and a bronze mirror.

- Spindle whorls’ and loom weights.

- Metal, especially bronze, was worked on site and a beautiful sheet bronze bowl was discovered.

- An antler shaker and a set of bar shaped dice that had dots representing the numbers three to six were found, suggesting that gaming may have been taking place.

Dice shaker and dice / Meare Lake Village finds – SWHT / Somerset Levels Project

Meare Lake Villages

For Bulleid and Gray the work on lake villages did not stop at Glastonbury; the find of some pottery in a peat field just north of the village of Meare led to the discovery of two more lake villages, ‘Meare East and West’. Bulleid and Gray excavated there from 1909 until 1956.

The Meare lake villages were built on a drying part of the raised bog just 100m north of Meare island and were bordered on their northern side by a large wet fen and open water that seasonally flooded the area of the settlements. Although there is considerable evidence of floors made of clay and wood with central hearths, only five examples appear to have been in roundhouses. Other posts formed simple lines like wind breaks and it appears that most of the area was occupied by either tents or open working spaces. There is considerable evidence for craft activities such as spinning, weaving, making artefacts of bone, antler and shale, beads of glass and objects of iron and bronze. Unlike the permanent settlement at Glastonbury lake village, Meare appears to have functioned as a seasonal market and possibly a meeting place for people from a much wider area.

The Villages today

Today the lake villages are scheduled ancient monuments and what remains lies buried, protected by the waterlogged ground. Whilst they may be out of sight, the fields where they lie have hummocks in ground very similar to the sight Arthur Bulleid would have seen over a century ago. Many of the actual objects that were found and photographs of the archaeologists are held in the Glastonbury Lake Village Museum at the Tribunal in Glastonbury town centre (currently closed).

2014 Lake Village dig. Centre image: close up of Birch bark over 2000 years old! – AMLP Staff

In 2014 sections of Glastonbury lake village were exposed to check on the preservation of the buried timbers. This work, funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund, was carried out by the South West Heritage Trust. It led to a project with the Internal Drainage Board to better control water levels on the site and thus improve conservation of the village for future generations.

Watch this film to find out more and see the archaeologists at work.

Click on the icon below and watch this interesting film. Once started don’t forget to click on the “square” icon (bottom right) to watch full screen and turn the volume up.

Credits

- Text based upon Richard Brunning’s book “Wet and Wonderful – The Heritage of the Avalon Marshes”

- Reference made to Sweet Track to Glastonbury by Bryony and John Coles.

Find out more about the heritage of the Avalon Marshes

Somerset’s Avalon Marshes’ landscape is perhaps best known for peat and water. These give the marshes their special character and have left a wonderful legacy of history and archaeology. For thousands of years people have been drawn to the area; once for food, fuel and safety; now for relaxation, wildlife and heritage.

Heritage Sweet Track